time <- c("Fri, Sept 22", "Sat, Sept 23", "Sun, Sept 24")5 Causality with Non-Experimental Data

In this section, we continue to evaluate causal claims, but this time we will not have the benefit of experiments.

Recall: Why do we use experiments?

We want to evaluate causal claims:

- Does manipulating one factor (a “treatment”) cause a change in an outcome? (\(Y_i(1) - Y_i(0)\))

- But we have a problem: the fundamental problem of causal inference

- (Can’t simultaneously both be treated and untreated - e.g., you can’t simultaneously be contacted and not contacted by a campaign)

- So instead, we randomly assign some units to receive a treatment, and some not to, and then compare their average outcomes in an experiment

And because of random assignment of the treatment, we can be confident that the groups are similar EXCEPT for the treatment

- Therefore, any difference between the two groups in average outcomes can be attributed to the treatment

But what if we can’t randomize the treatment?

5.1 Why can’t we always experiment?

Example: Do political leaders tend to matter for democracy?

- Our outcome: how democratic nations are

- Our causal effect of interest:

- On average, how democratic nations are with their current leaders -

- On average, how democratic nations would be with different leaders

- Possible Experimental Designs to randomly assign half of countries to receive a different political leader

- Rig elections (I.e., Election fraud- Illegal, unethical)

- Forcibly remove half from office (Probably illegal)

- Assassinations (Illegal, Immoral, Unethical, etc.)

Again, we have problems!!

5.1.1 What can we do instead?

Let’s say we want to make a causal claim about the effect of one variable on an outcome, but we can’t think of an experimental design that will help us estimate this.

What do you do?

5.2 Causal Identification Strategies

Our goal: Try to “identify” the causal effect of one variable on an outcome. As Montell Jordan once said, this is how we do it:

- Use data we have (that exist out in the world)

- Compare those who are “treated” to a relevant comparison group who is not treated

However, we can’t randomize treatment so….

- We do our best to try to choose a good comparison (one very similar to the treatment group, but happens not to be treated)

We want to rule out all possible confounding variables and “alternative explanations” for the outcomes we observed.

5.2.1 Example: Travis Kelce Jersey Sale and Instagram Gains

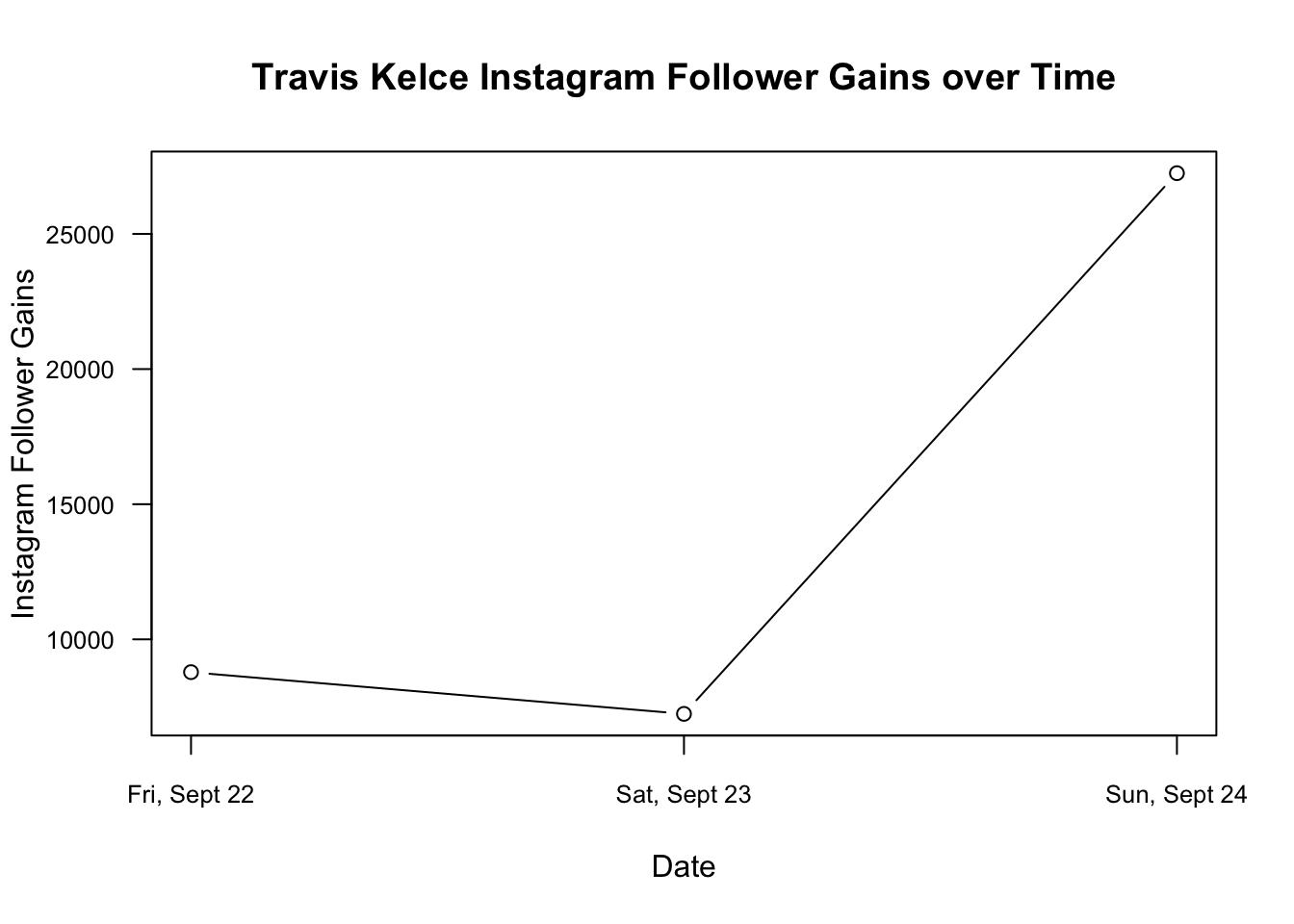

Why did Travis Kelce experience an increase in social media followers?

- Let’s use the

plot()function to visualize this- Kelce saw an increase in followers on Fri, Sept 22 of 8786

- Kelce saw an increase in followers on Sat, Sept 23 of 7242

- Kelce saw an increase in followers on Sun, Sept 24 of 27249

- When visualizing a trend, we put time on the x-axis

- We put the values of the outcome on the y-axis

followers <- c(8786, 7242, 27249)5.2.1.1 Line Plots

To make it a line plot, we add type = "l" or type = "b".

- Note: Because our time is text-based, we cannot add it to the plot directly. Instead, we use a placeholder

1:length(time). - Instead, we add

xaxt="n"to remove the default x-axis and addaxis()below the plot code to add our own custom axis. By adding the “1”, we are indicating it should be drawn on the x-axis

plot(x=1:length(time), y=followers,

type="b",

main = "Travis Kelce Instagram Follower Gains over Time",

ylab="Instagram Follower Gains",

xlab="Date",

xaxt="n",

las=2, cex.axis=.8)

axis(1, at=1:length(time), labels=time, cex.axis=.8)

YOUR TURN: Make a causal claim about the increase in Kelce’s followers

- What is the outcome? the number of followers

- What is the treatment? what do you think caused the increase

- What are the two counterfactual states of the world under treatment vs. not under treatment?

Is this a Taylor Swift effect?

- How could we prove it? What are possible confounders?

- Maybe it’s just the effect of playing a game on Sunday?

- Maybe all NFL players experienced a similar increase?

- Maybe Kelce had a particularly good game relative to other players?

5.2.3 Causal claims from before vs. after comparisons

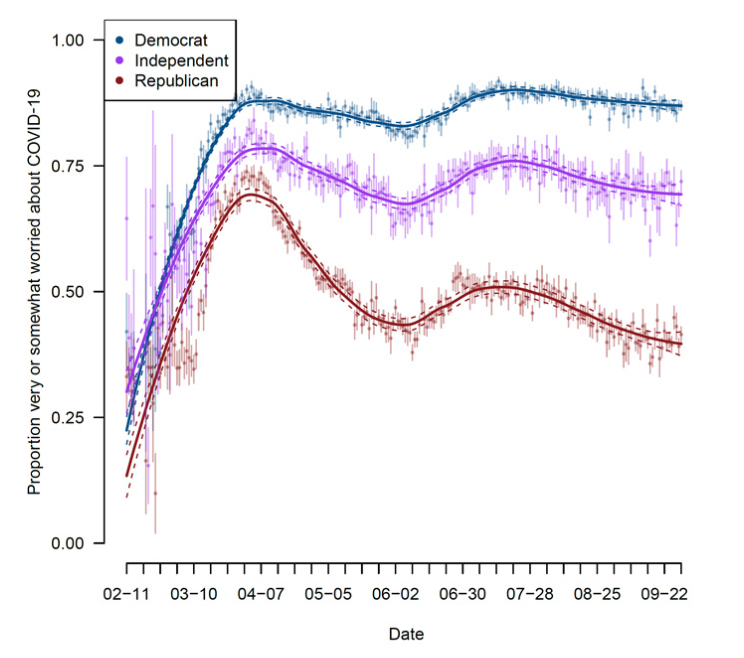

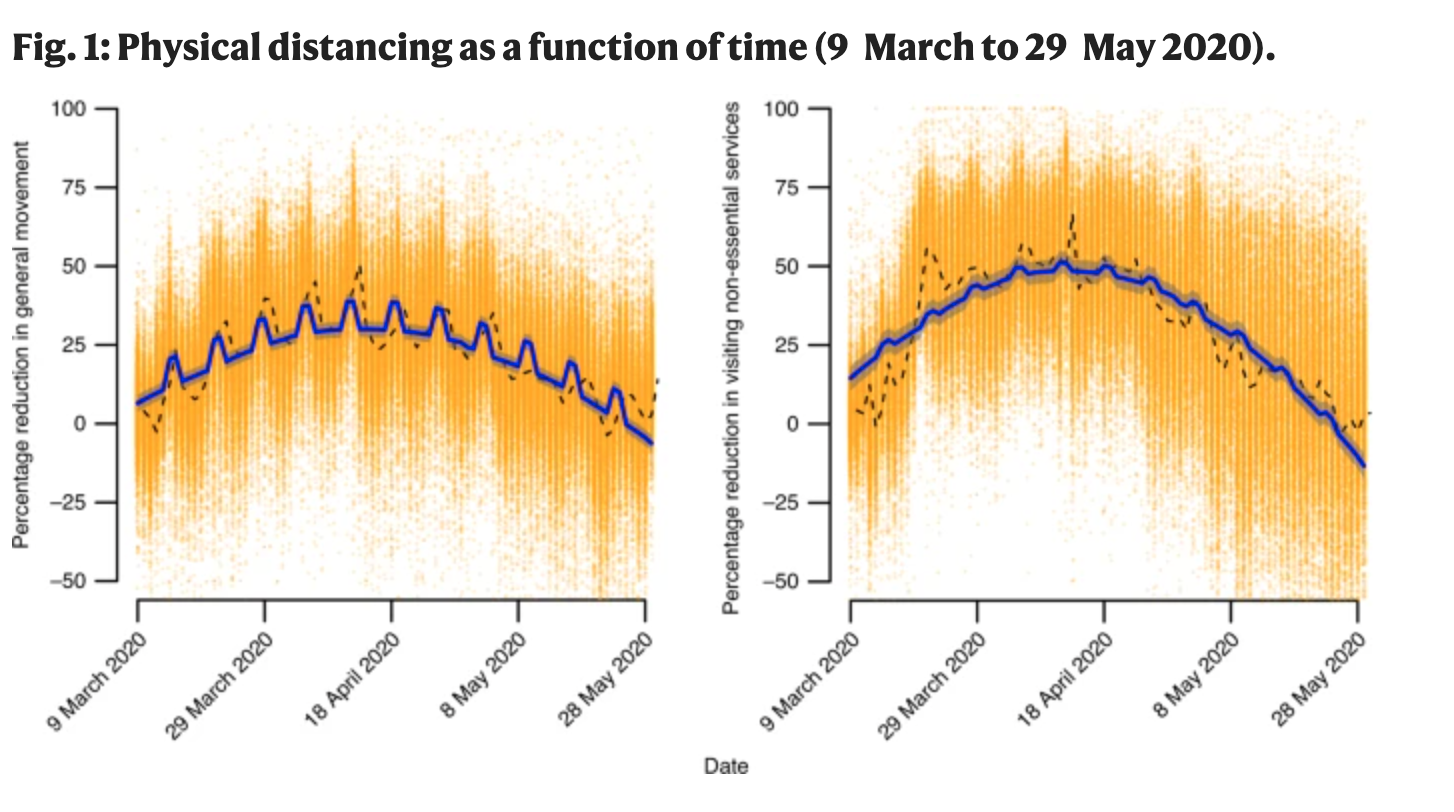

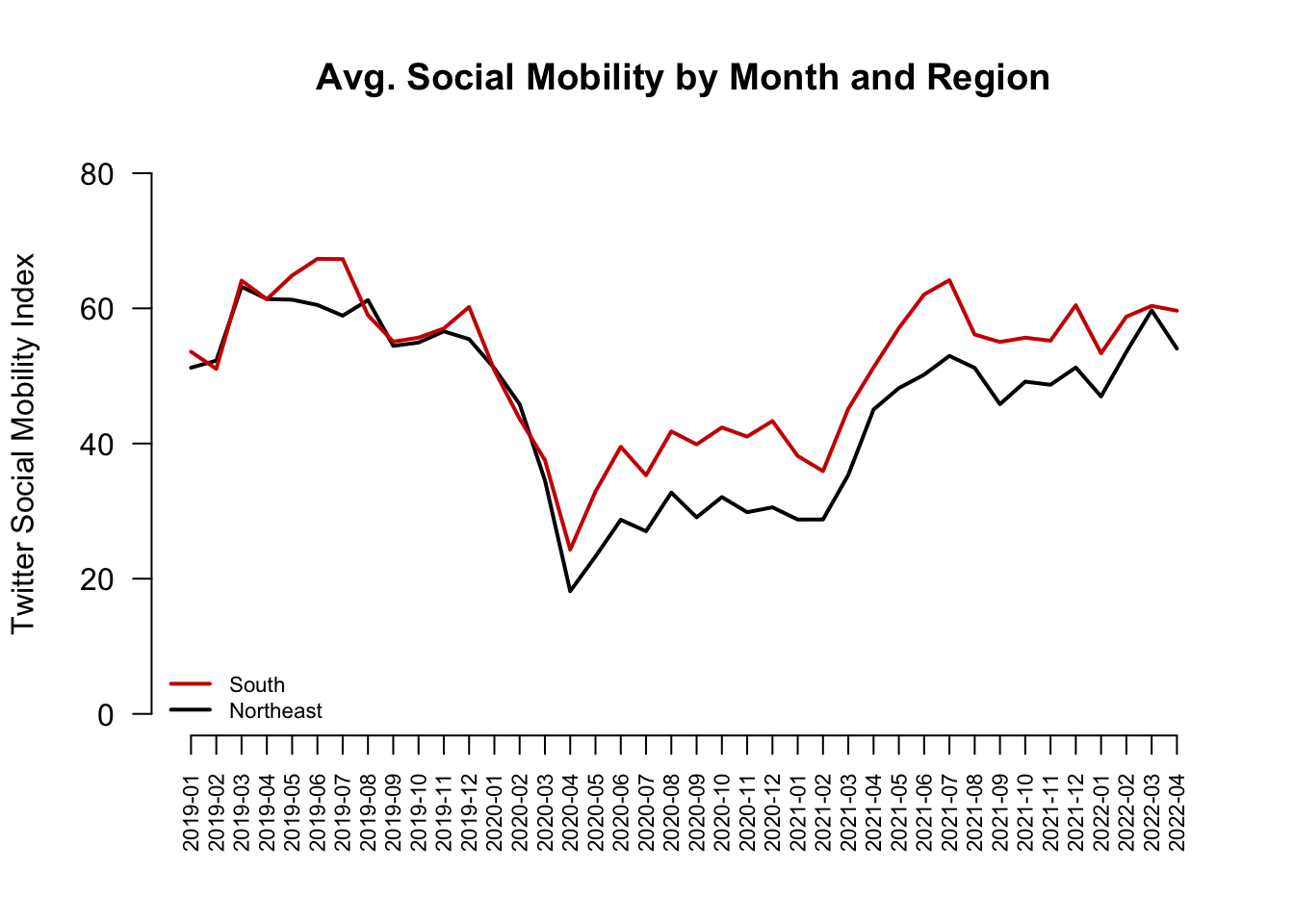

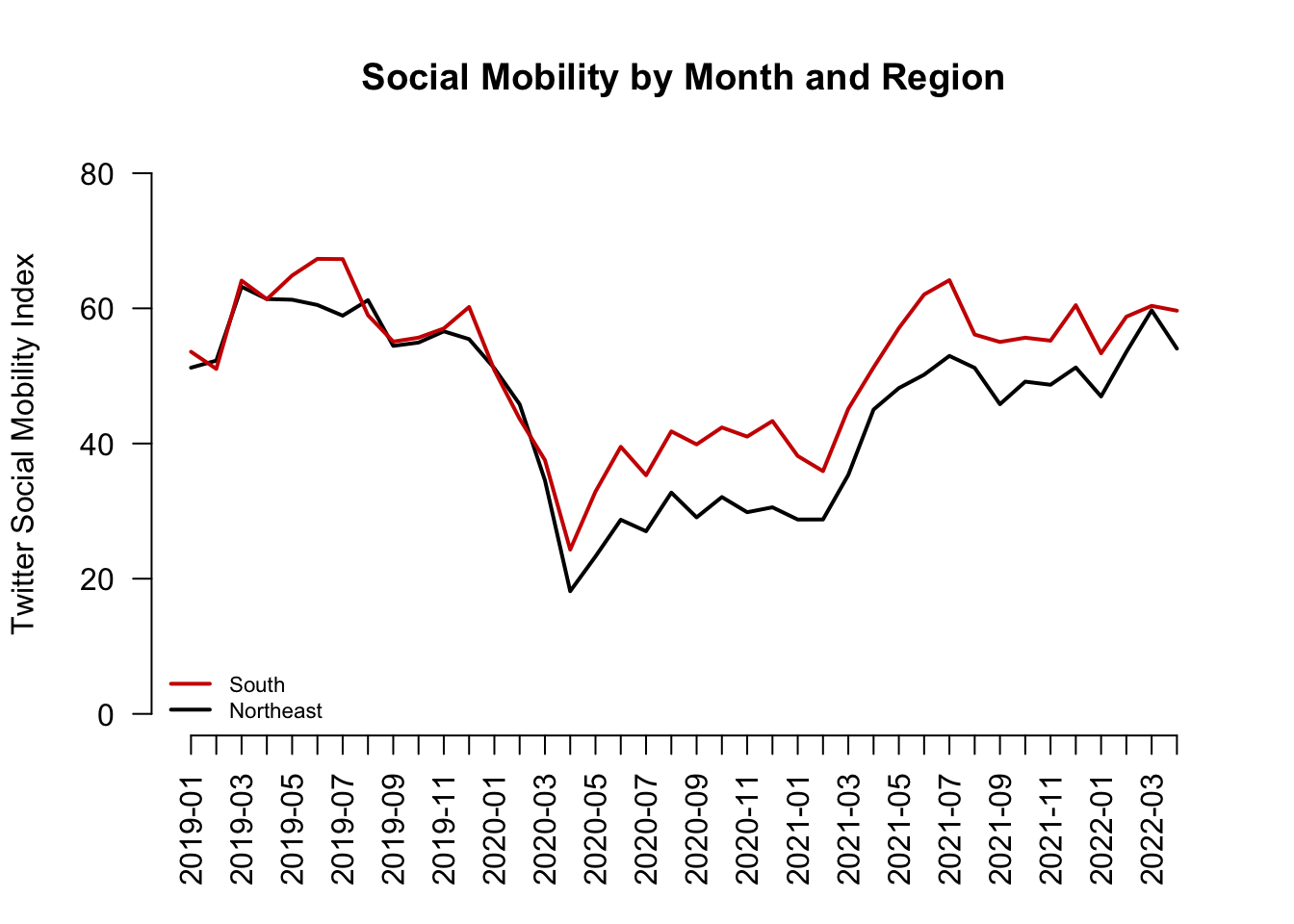

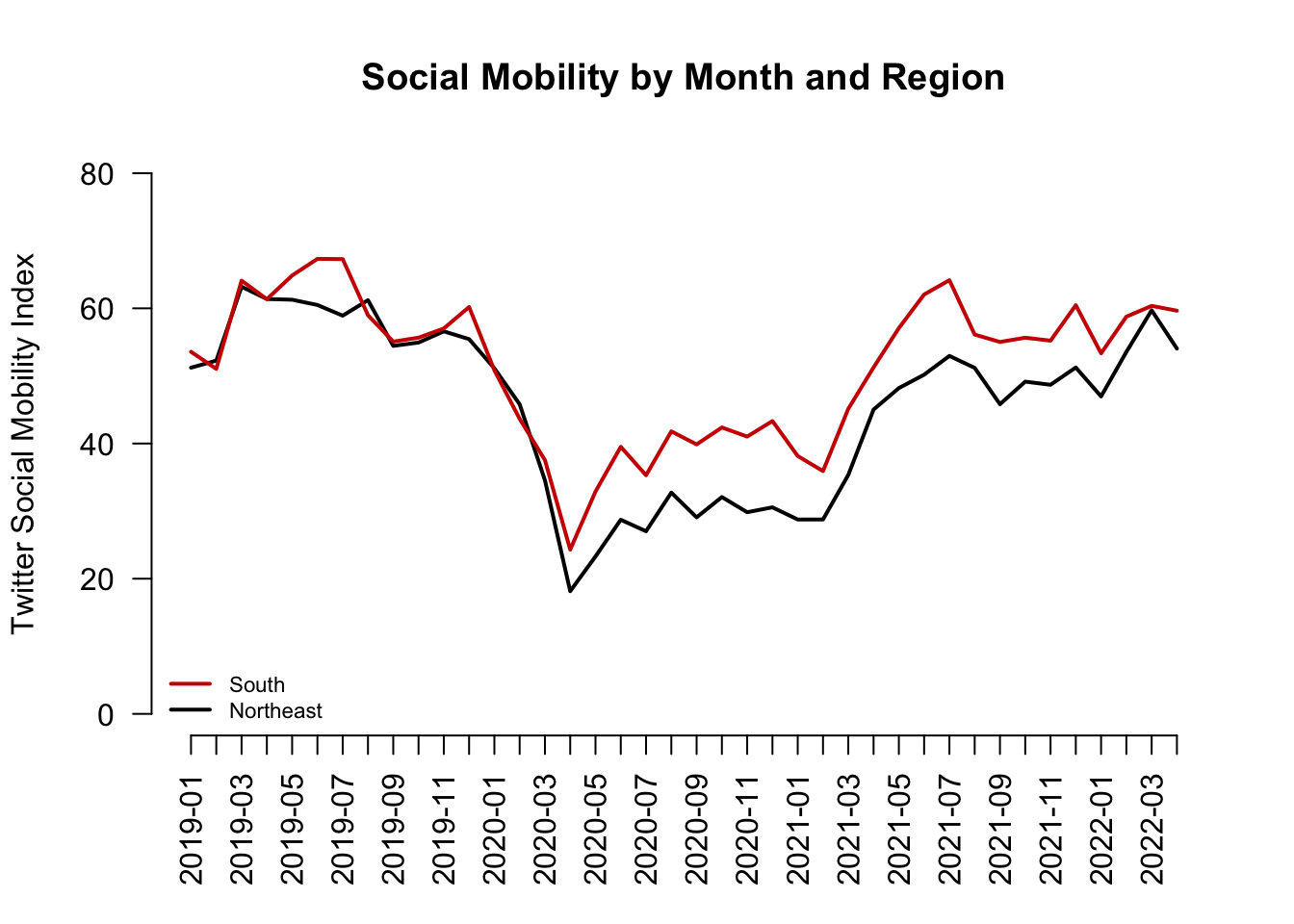

What types of research questions could these trends generate?

What would you want to know about how movement has changed over time. Think about examples of causal claims you might make:

- Example: X caused mobility to decline

- Example: Z caused mobility to decrease

- Example: W caused mobility to increase at different rates across different regions.

So what can we do to test causal claims?

- What is the fundamental problem of causal inference in this case?

- Can we do an experiment?

- Researchers try to form comparison groups, in a strategic way, with the data they have (i.e., “observational” or “non-experimental” data).

- Because they cannot randomly assign two different experiences of the world, instead they choose two cases or two groups of cases that

- Seem extremely similar except

- One has the treatment of interest, and one does not

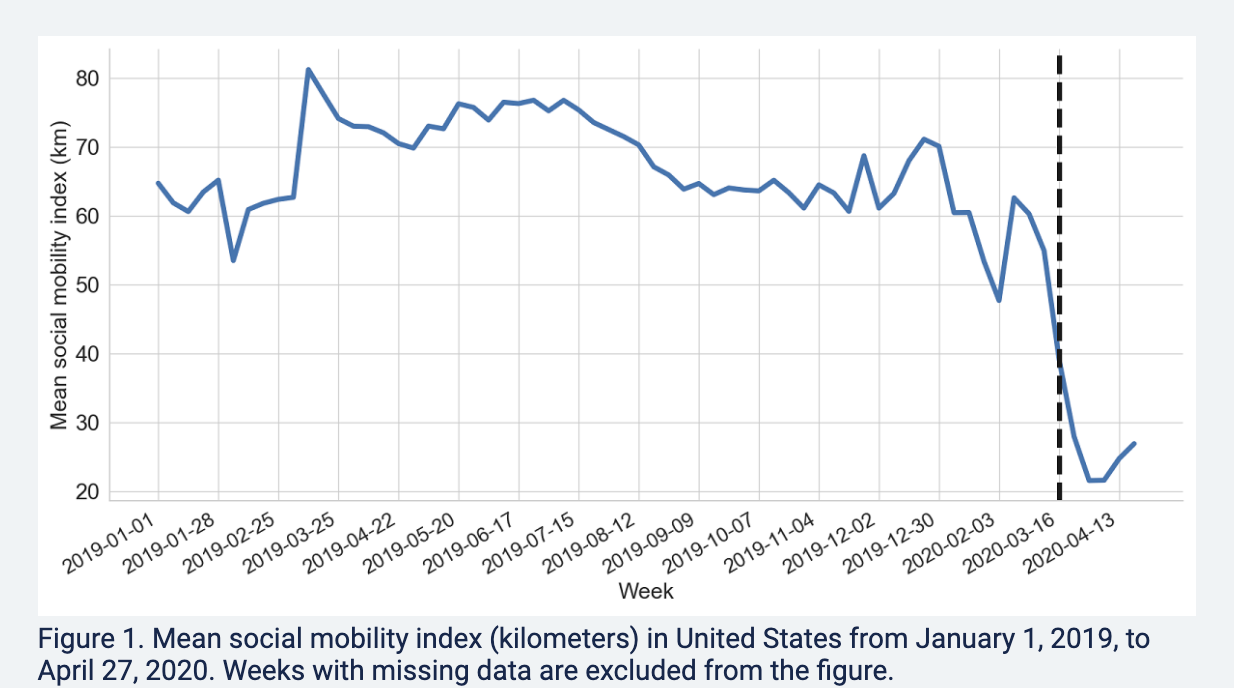

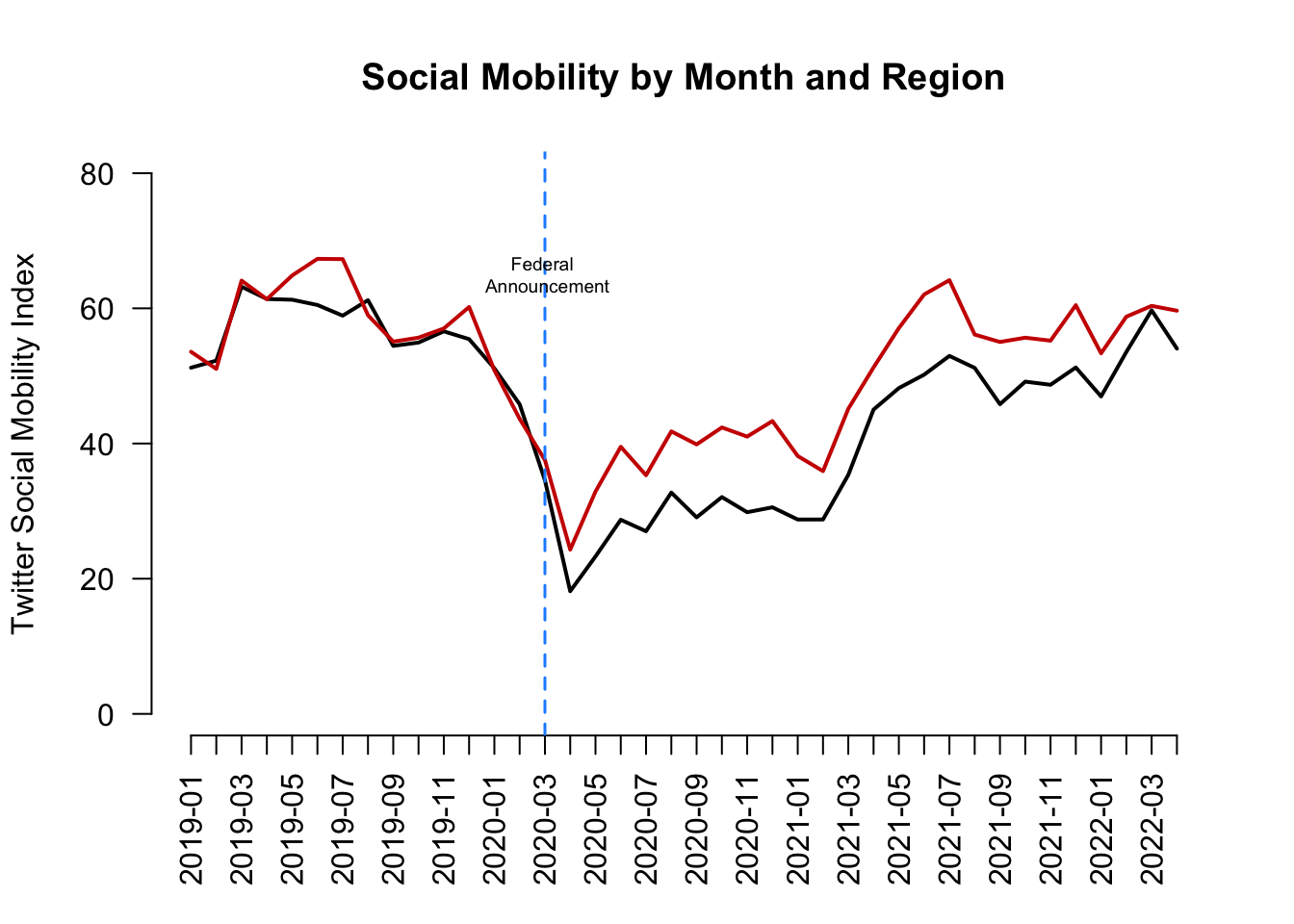

Example: Before vs. After Comparison

Let’s examine social mobility just before vs. just after the federal announcement of social distancing guidelines to stop the spread of COVID-19.

- To do so, we will draw a vertical line at March 2020

- Note we use

abline(v=)to indicate a vertical line at a location to cross the x-axis

- Note we use

This is the 15th entry in our vector, which means at point 15 on the x-axis.

mobilitybymonthNE["2020-03"] 2020-03

34.55917 mobilitybymonthNE[15] 2020-03

34.55917 - We will also add text to inform views what that line represents

- Note we use

text(x= , y=, labels)to indicate where to put text

- Note we use

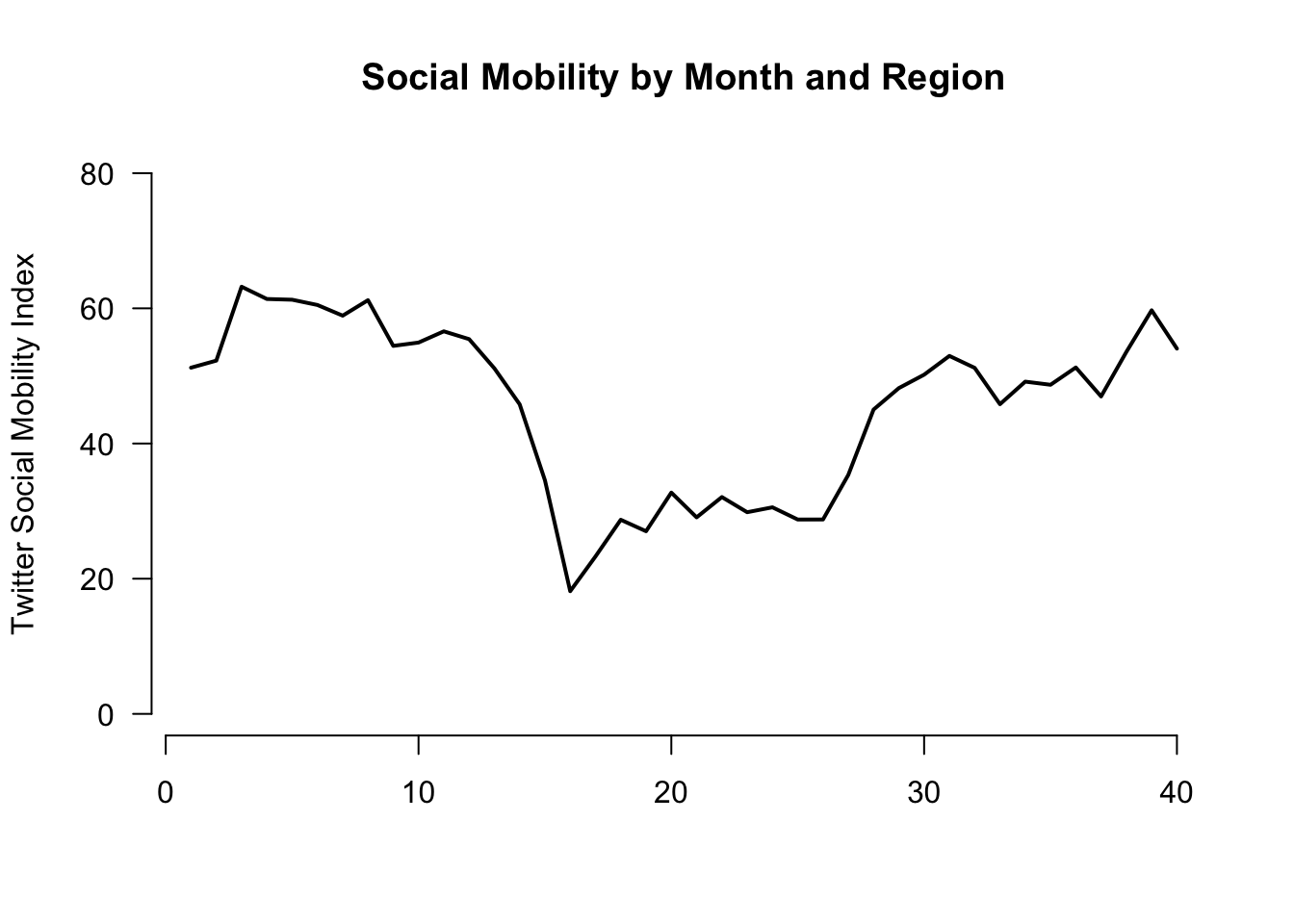

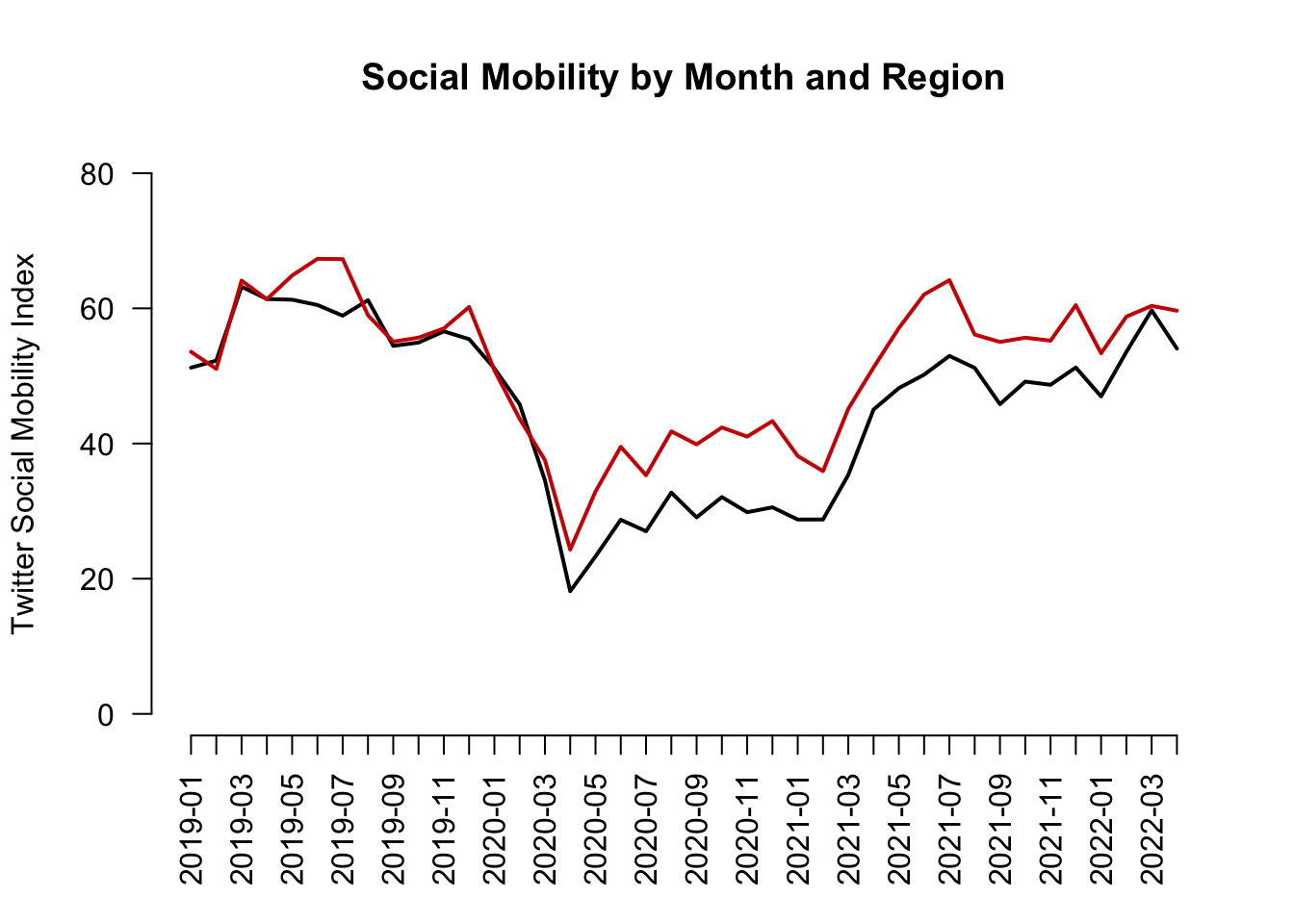

plot(x=1:length(mobilitybymonthNE),

y=mobilitybymonthNE,

type="l",

main="Social Mobility by Month and Region",

ylab="Twitter Social Mobility Index",

xlab="",

ylim = c(0, 80),

las=1,

lwd=2,

bty="n",

xaxt="n") # removes original x-axis

## Add line to the plot

lines(x=1:length(mobilitybymonthSO),

y=mobilitybymonthSO, col="red3", lwd=2)

## add the axis the "1" means x-axis. A "2" would create a y-axis

axis(1, at = 1:length(mobilitybymonthNE),

labels=names(mobilitybymonthNE), las=2)

## add dashed blue vertical line

abline(v=15, lty=2, col="dodgerblue", lwd=1.5)

## add text near the line

## the \n breaks the text into different lines

text(x=15, y=65, labels = "Federal \n Announcement", cex=.6)

We see mobility does appear to be lower after the announcement relative to before the announcement. Is this causal?

- Assumption: We would want to be able to argue that social mobility in the weeks following the announcement (after time period) would look similar to social mobility in the weeks prior to the announcement (before period) if not for the federal announcement

- That the before vs. after time periods would be similar in any meaningful way if not for the presence of the treatment in the after period.

Does this seem like a plausible argument? Could other things (confounders) occurring around the time of the federal announcement also have caused the steep decline in social mobility?

- If we think something else happened around the same time that might have caused mobility to go down anyway, then we may be doubtful that this is a causal effect.

5.3 Three Common Identification Strategies

Example: Does drinking Sprite make a person a better basketball player? (Inspired by 1990s commercial where a kid believes drinking Sprite will cause him to play basketball better.)

- Cross-section comparison: Compare Grant Hill (who drinks Sprite) to others (who don’t)

- Before-and-after: Compare Grant Hill after he started drinking Sprite to Grant Hill before

- Difference-in-differences: Compare Grant Hill before and after drinking Sprite and subtract from this the difference for some other person (who never drank Sprite) during the same two periods

(Note: “drinking Sprite” is our treatment.)

5.3.1 Threats to Cross-Section Designs

Assumption: Must assume no confounders and any alternative explanations related to differences between the treated and control subjects that also relate to the outcome. The Threat: Your two groups may differ in ways beyond the “treatment” in ways that are relevant to the outcome you care about.

- Compare Grant Hill, a tall NBA player who currently drinks Sprite (treatment group) to

- Yourself, assuming you and they do not drink Sprite (control group)

- Compare your basketball skill levels (the outcome).

- Suppose Grant Hill is better (a positive treatment effect).

- Can we conclude Sprite causes a person to be a better player?

Nope, because other things that affect basketball talent differ between you and Grant Hill, and these things, not Sprite, may explain the difference in basketball talent.

Moreover, even if we compared just among NBA players (Grant Hill vs. non-Sprite drinking players of his era), it’s possible that Sprite targeted all-stars to recruit to drink Sprite. In this way, pre-existing basketball talent (a confounder) both explains why Grant Hill drank Sprite (relates to the treatment) and explains his higher level of basketball talent (relates to the outcome) in the time period after drinking Sprite.

- For a cross-sectional comparison to be plausible, we need to choose a very similar comparison in order to isolate the treatment as the main variable that is causing a change in an outcome.

5.3.2 Threats to Before-After Designs

Assumption: Must assume no confounding time trend. Threat: Something else may be changing over time, aside from the treatment, that is affecting your outcome.

- Compare Grant Hill in the years after he started drinking Sprite (treated) to

- Grant Hill the years before he started drinking Sprite (control)

- Compare his basketball skill levels (outcome).

- Suppose Grant Hill after Sprite is better (a positive treatment effect).

- Can we conclude Sprite causes a person to be a better player?

Not if something else Grant Hill started doing during that time period made him better (e.g., maybe during that time the NBA provided higher quality coaches and trainers, and everyone (including Grant Hill) got better).

- You want your treatment to be the only thing relevant to basketball talent changing over time.

5.3.3 Threats to Diff-in-Diff Designs

Assumption: Must assume parallel trends: That in the absence of treatment, your treatment group would have changed in the same way as your control

- Compare Grant Hill in the years before vs. after he started drinking Sprite to Grant Hill’s teammate, who never drank sprite, in the same two time periods (before Hill drinks Sprite vs. after Hill drinks Sprite)

- Compare the change in each player’s basketball skill levels. Suppose Grant Hill’s skills increased to a greater degree than his teammate’s over the same time period.

- Can we conclude Sprite causes a person to be a better player?

If we are confident that Grant Hill did not have a unique (non-Sprite) advantage over that time period relative to other players, then our assumption might be plausible– that Grant Hill and other players would have experienced a similar growth in their skills if not for Grant Hill getting the extra benefit of Sprite.

Instead, if, for example, Grant Hill got a new trainer during this period AND his teammate did not, then we might have expected Grant Hill to see more improvement even if he didn’t start drinking Sprite. A violation of the parallel trends assumption!

- Causality is hard!

5.4 Application: Economic Effects of Basque Terrorism

Research Question: What is the economic impact of terrorism?

- Factual (\(Y(1)\)): Economy given Basque region hit with terrorism in early 1970s

- From 1973 to late 1990s, ETA killed almost 800 people

- Activity localized to Basque area

- Counterfactual (\(Y(0)\)): How would Basque economy have fared in the absence of the terrorism?

- Basque was the 3rd richest region in Spain at onset

- Dropped to the 6th position by late 1990s

- Would this fall have happened in the absence of terrorism?

Problem: We can’t observe the counterfactual. We can’t go back in time to manipulate the experience of terrorism.

5.4.1 Applying 3 Identification Strategies

- Compare Basque to others after 1973 (Cross-section comparison)

- Compare Basque before and after 1973 (Before-and-after)

- Compare others before and after 1973 and subtract the difference from Basque’s difference (Difference-in-differences)

For a video explainer of the code for this application, see below. (Via youtube, you can speed up the playback to 1.5 or 2x speed.)

basque <- read.csv("basque.csv")head(basque) region year gdpcap

1 Andalucia 1955 1.688732

2 Andalucia 1956 1.758498

3 Andalucia 1957 1.827621

4 Andalucia 1958 1.852756

5 Andalucia 1959 1.878035

6 Andalucia 1960 2.010140Variables

region: 17 regions including Basqueyear: 1955 – 1997gdpcap: real GDP per capita (in 1986 USD, thousands)

Subset Basque Data into Four Groups

## Basque before terrorism

basqueBefore <- subset(basque, (year < 1973) &

(region == "Basque Country"))

## Basque after terrorism

basqueAfter <- subset(basque, (year >= 1973) &

(region == "Basque Country"))

## others before terrorism

othersBefore <- subset(basque, (year < 1973) &

(region != "Basque Country"))

## others after terrorism

othersAfter <- subset(basque, (year >= 1973) &

(region != "Basque Country"))What is the economic impact of terrorism?

Cross-section comparison

mean(basqueAfter$gdpcap) - mean(othersAfter$gdpcap)[1] 1.132917Before-and-after design

mean(basqueAfter$gdpcap) - mean(basqueBefore$gdpcap)[1] 2.678146Difference-in-Differences design

treatDiff <- mean(basqueAfter$gdpcap) -

mean(basqueBefore$gdpcap)

controlDiff <- mean(othersAfter$gdpcap) -

mean(othersBefore$gdpcap)

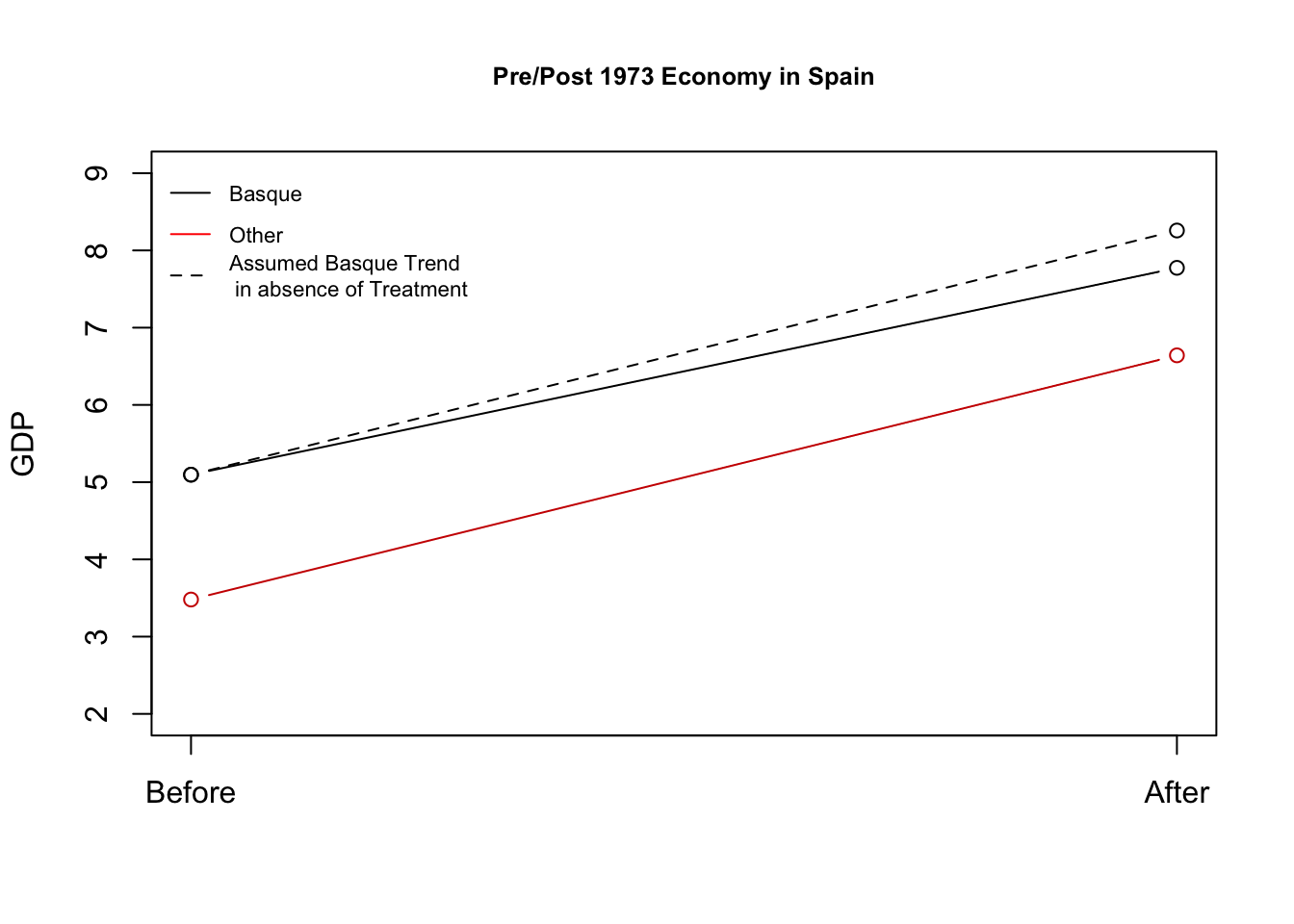

treatDiff - controlDiff[1] -0.48316Here is a way to visualize this difference-in-differences. Our estimated causal effect is the difference between the observed post-1973 economy in the Basque region mean(basqueAfter$gdpcap) and what we assume the economy would have been in the absence of terrorism (the treatment) using the dotted line– adding the control group’s trajectory to the pre-1973 Basque economy (mean(basqueBefore$gdpcap) + controlDiff).

What should we conclude from each approach?

- Each approach resulted in a different estimate of the impact of terrorism on the economy. We should choose the approach for which we think the underlying assumptions are most plausible.

5.5 Placebo Tests

Which Results Should We Believe? Role of Placebo Tests

Cross-section comparison

## were there pre-existing differences between the groups?

mean(basqueBefore$gdpcap) - mean(othersBefore$gdpcap)[1] 1.616077Before-and-After design

## was there a change in a group we don't think should have changed?

mean(othersAfter$gdpcap) - mean(othersBefore$gdpcap)[1] 3.161306What about the Difference-in-Differences design?

## here we go back in time even further to examine "pre-treatment" trends

## we want them to be similar

(basqueBefore$gdpcap[basqueBefore$year == 1972] -

basqueBefore$gdpcap[basqueBefore$year == 1955]) -

(mean(othersBefore$gdpcap[othersBefore$year == 1972]) -

mean(othersBefore$gdpcap[othersBefore$year == 1955]))[1] 0.07147071These “placebo” checks are closest to zero for diff-in-diff, so we may believe that the most.

Thanks to Will Lowe and QSS for providing the foundations for this example

5.6 Wrapping Up Causality

Do you get this joke?